Education, Labor and Sustainability

Lots of notebooks. I kept lots of physical notebooks during my ‘Sopractical’ graduate program at Portland State University, where Jen Delos Reyes shared her radiant self with us all. As an educator, she went beyond her call of duty, finding artists and books to offer each student after we presented an idea or a project for critique. Critique was not really what one could call what our program offered; instead it was idea generation, thoughtful notes on context, and a sense of collaboration, group work, and multiple authorship. We learned little through theory. Instead we learned through practicing the social, making projects, and labor. Open Engagement (OE) was one of the most important of these learning tools, at the time unique to our program.

Organizing came naturally to me, and volunteering for a worthy cause was the only way I knew how (I hadn’t yet been indoctrinated by the Creative Capital boot camp). The payback was rich: an intimate knowledge of who was making Socially Engaged Art across the country and the world, a chance to work with phenomenal artists and thinkers, an opportunity to dream up the ideal experience for each new conference, thoughtfully taking into mind the feedback offered from previous years’ attendees. Looking through my stacks of notebooks marked for having Open Engagement content, I found quotes and artists and projects to look up, but mostly, I found to-do lists.

My labor, like everyone else’s on the all-woman team, including Jen’s, was exploited by a system that does not value it. I remember in 2010 gathering a crew of about twenty volunteers to help make tote bags designed by Helena Keefe and Lea Redmond, who lived in Oakland. Inviting Portlanders to draw their favorite food carts, Helena and Lea designed a pattern from their renderings. With Ariana Jacob’s help, we found a skilled printmaker to lead a slew of us through the multicolor screen print process. Somehow we finagled a completely unrelated sewing studio to train another ten student volunteers to sew the bags in their studio. The beautiful bags were given out for free to conference goers, who paid nothing (other than travel expenses for some) to participate in this three-day extravaganza of renowned artist-speakers, idea generators, participatory projects, organized bike rides, home stays, and meals.

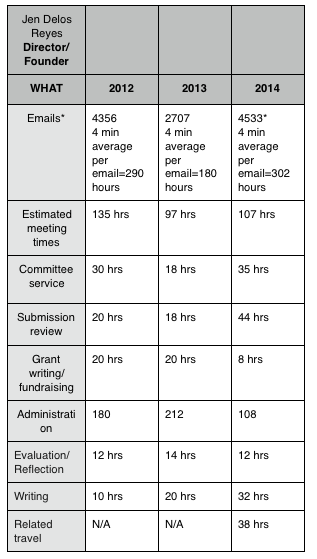

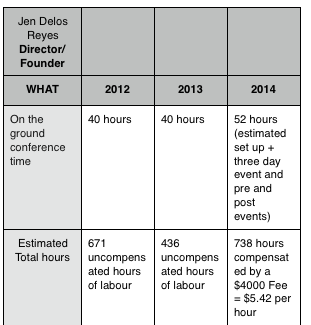

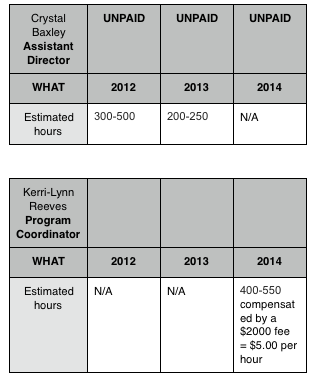

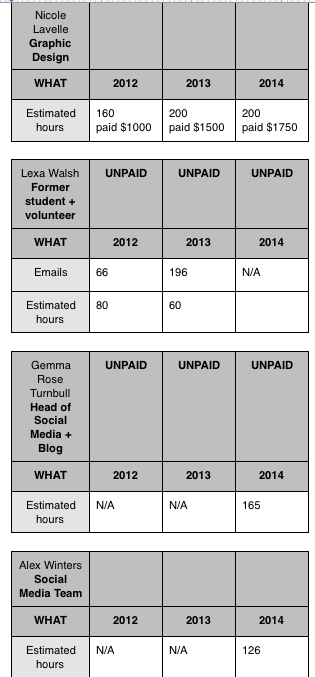

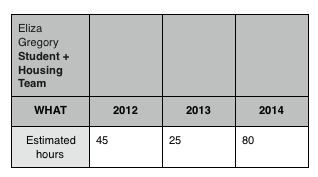

It is not new that arts labor, and women’s labor, is both underappreciated and under recognized. Jen realized how unsustainable it was to continue in this vein for both her team and herself and planned on writing an essay “What is the Value of a Free Conference?”1 In 2014, she sent an email to the OE team, asking each of us to count our roles and collective hours for every year up to that point. 2010: Project manager, organizer, presenter, 80-100 hours, unknown emails as account had expired. 2011: Party planner, Field Work manager, presenter, 80 hours, 114 emails. 2012: Hospitality, Portland Art Museum liaison, presenter, 80 hours, 66 emails. 2013: Organizer of attempted then aborted (due to logistics/funding) dinner, food-based projects manager/curator, presenter, 80-100 hours, 196 emails. These hours weren’t counting the conference weekends, and weren’t even close to Jen or Crystal’s, however there were several other team members whose hours (and emails) were comparable with mine. While we were happily donating this work, knowing its rewards were great, Jen wanted something different for us.

In 2016 Suzanne Lacy asked OE participants to air suggestions at the post-conference master class. To my disbelief, tens of complaints were angrily shouted out about the conference because for the first time in seven years, it cost attendees money to attend. $50 now bought you 4-5 days jam-packed with speakers, projects, workshops, tours, and parties, including talks by Suzanne and the inimitable Angela Davis. The conference was still free to presenters, who were the only people present this day. Volunteering still bought you access. I looked over at Crystal Baxley, the most under recognized and hardest working laborer on OE’s team, her exhaustion peering from behind her glasses and unusually messy hair. She was too tired to defend herself. That year, for the first time, many of us were finally getting paid for our labor. After six or so iterations of OE where my skilled labor was utilized, I was getting paid a symbolic fee for months of work. We were finally getting paid for our years of labor, yet our labor was completely unrecognized and unappreciated by these conference presenters. I stood up and announced this fact. Eliza Gregory stood up and suggested if these people wanted a free conference, they could help volunteer, help fundraise for it, or become a fellow Open Engagement worker. Suzanne, realizing she had created a bit of a clusterfuck, eventually tried to facilitate reconciliation with the rowdy crowd. I might have said, too, “… guess what everyone, conferences cost money and work to produce… If only you knew how much!”

This crowd, like many before them, were given an opportunity to offer critical feedback a few weeks later, an opportunity OE offers to all of its attendees, which results each year in applied changes whenever feasible to make the conference as open as possible. One of the legacies of OE for me is to think about sustainability, not only in how be malleable, but also in how to organize a conference, and my practice. Thanks to the work of artists and advocates like Creative Capital, W.A.G.E. (whom I learned about at OE) and The Present Group, I’ve become skilled at getting paid for my labor as an artist. I still joyfully volunteer when it is appropriate. I’m happy to report Open Engagement is paying its team better than ever. Sustainability has more than just money at stake: there’s also the sustainability of self and practice, particularly as we live in times of crisis. To make Socially Engaged Art sustainable for myself, I have to get off the computer and back into the studio. Hopping into the sauna at the Y a few times per week helps too. I look forward to hearing about what you are all doing to keep yourselves and practices alive as we move onward, bidding a fond, sweet farewell to OE.

-Lexa Walsh is an artist and cultural worker based in Oakland, CA, and a long time agent of Open Engagement. www.lexawalsh.com

1 Below is the unfinished essay from 2014 and notes by Jen Delos Reyes referenced by Lexa Walsh in this post.

What is the Value of a Free Conference?

Jen Delos Reyes

What is the real cost of a free conference? This question was put forward at the close of 2012 at our closing panel discussion by a group of students who were involved in organizing a line of programming at Open Engagement that explored economies. The question was met with uproarious applause. We were asked to evaluate what does “free” really mean? Someone is always paying, and who pays has significance. There are underlying issues that have a reach far beyond a conference on socially engaged art: Who is paid? Who is not? Who is valued? How does one pay? At what cost? Examining the conference year by year, these questions will be explored through looking at the funding, support, and personal costs that have made the conference possible. What follows is an examination of the labor, cost, and contributions that made open engagement possible since 2012.

I want to re-frame the original question from 2012 by asking What is the real value of a free conference? How can this conference on all levels be a proposal for a structure that does not yet exist, and model how to be in our world in a different way. We need to address the deeper economies at play. As Open Engagement moves forward it has the potential to not only highlight, mobilize, and strengthen existing networks of support through a receptive mobility, but to also in itself serve as a model. There is much work to be done for this conference to reach that state, the first step toward forward movement is acknowledging where we are.

I do not wish that the conference continue in solidarity as a precariat, as I hope that this state is one that will not continue to be the case for so many of us artists and adjunct laborers. Let us think of what sustainability can mean for one another. I believe that Open Engagement does have value, but a question that must be asked is what is that value worth if the cost is continuing to perpetuate economies and systems of labor that are untenable? The emergent value that Open Engagement has the possibility to embody is to become a model of sustainability for socially engaged art practice, institutions, and workers. Open Engagement is not about an exodus from institutions, or the creation of a new one. It is about working with institutions to realize sustainable models for socially engaged contemporary art practices.

What model can we present for 2015?

WHY IS OPEN ENGAGEMENT “FREE”?

Since 2007 Open Engagement has maintained its position as a free conference. How this is possible is a combination of resourcefulness, shifting what a system can do/who a system is for, institutional support, and countless hours of invisible and uncompensated labor. What kind of space does something that is free create? What does it mean that what creates that “free” space is an art practice? What are it’s unique potentials? In Irit Rogoff’s essay Free she outlines several relevant questions:

- First and foremost what is knowledge when it is “free”?

- Whether there are sites, such as the spaces of art, in which knowledge might be more “free” than in others?

- What are the institutional implications of housing knowledge that is “free”?

- What are the economies of “free” that might prove an alternative to the market-and-outcome-based and comparison-driven economies of institutionally structured knowledge at present?

p.184

In relation to OE from 2007-2013 this “free” site of knowledge was hosted by universities that otherwise charge for the distribution of knowledge. Funds were redistributed in order to create an institutionally supported site of public knowledge sharing. This created a shift the economy of knowledge sharing. The conference being free has the ability to emphasize a different kind of exchange. The exchanges we seek to further is the conference as a hub for the transmission of knowledge and site to the further support artists working in these ways.

THE COST OF OPEN ENGAGEMENT

Open Engagement, like many of you who are reading this, sustains a precarious existence. The conference has no guaranteed income. It is important to keep the perspective that Open Engagement, while it stems from an artistic practice, is ultimately a conference. It is not an exhibition. Artist fees, and speaker fees (with the exception of keynote presenters and often workshop leaders) are not usually compensated within this model. What is standard practice is that conference presenters and attendees pay fees to the conference to attend and participate as a speaker. Unlike the standard conference practice of charging presenters a fee to attend without compensation, Open Engagement has intentionally chose a position different than that model. When WAGE breaks down the payment of artist fees and compensation they do this in relation to an institutions revenue and operating budget. Open Engagement is a non-revenue generating operation. Every year that I have organized this conference I have done it like it was going to be the last time. This was not just in the spirit of doing things to the best of our abilities, but mostly the reality of not knowing if there would be funds to continue.

In 2007 the funds for the conference came from a grant to support my graduate work and research, which I chose to conduct in the form of a conference on socially engaged art. The conference was realized for under $10,000 plus non-monetary support from partnering organizations and individuals. In 2010 the funds for the conference came from a grant from the Regional Arts and Culture Council in Portland, OR. The conference was realized for $6000 plus non-monetary support. In 2011 I made the case to Portland State University that Open Engagement is a site of education, both for the students involved, and the public. It made sense to me that I program focused on socially engaged art could work to create a site that would widen the field and make this free and public. The university created a $10,000 budget to make Open Engagement more sustainable. In addition to this budget we sought sponsorships from other programs focusing on socially engaged art. The conference was realized for $15,000 plus non-monetary support from partnering organizations and individuals. In 2012 and 2013 the PSU support continued, we received another RACC grant, and continued sponsor support. Both conferences were realized for between $18,000-$20,000 respectively plus non-monetary support. Now in 2014 thanks to primary support of our partners the Queens Museum and A Blade of Grass, as well as with contributions from sponsors, and early bird registration donations we are working with $23,000 and offering an expanded conference program and compensating almost all of the people working on the conference.

FREE AND UNDERPAID LABOR AND OPEN ENGAGEMENT

We get by on very little, and we are without a doubt working too much. There are monetary costs, the cost of support that is donated, and personal costs. I don’t want artist run, and artist supported culture to be synonymous with little pay, or no pay. For myself personally one of the biggest personal costs has been that I have worked uncompensated on Open Engagement, no fee taken as director, and no compensation or release time from the academic hosts. I don’t do this because I have money or generational wealth to sustain myself. I was raised by a poor immigrant mother who to this day does not have savings. We moved 18 times in 23 years because of housing insecurity. I am the first person in my immediate family to graduate from college. As an adjunct and then fixed term (and then adjunct again) faculty I did not even receive the “value” of the conference being seen as “institutional service” or padding for tenure review.

One of the most important things that have changed with the move of Open Engagement to the Queens Museum for 2014 is that there are now more paid staff working on the conference than ever before. Thanks to the paid staff labor from the Queens Museum there are now only five people who are donating time to OE, where as in the past there were not even five paid staff, in fact, there was usually only one and that was a paid graduate assistantship. In addition the Queens Museum is also paying for invited workshop leaders through their Open Air program.

These graphs chart the expended labor and contributions of a selection of people who have worked on and are currently working on Open Engagement.

*These numbers account only for personal email from my own account and does not account for the emails sent to the conference email address.

*This number is as of 03/26/2014. I receive between 10-25 OE emails per day on average.

WOMEN AND OPEN ENGAGEMENT

As you might have noticed from the charts of contribution of labor, there are a lot of women that work on Open Engagement. What does it mean that the labor for this was done primarily by women year after year for free or for less than minimum wage? From the direction, to the graphic design, social media, committee members, and volunteers year after year the overwhelming majority of the people who push Open Engagement forward are women. Open Engagement year after year is driven by women, volunteering their time, or being under-compensated. A large part of how we are able to pull off Open Engagement for so little is that very few people are paid for their work aside from the keynotes, designers, and now Program Coordinator and the director. In Marilyn Waring’s 1999 book “Counting For Nothing: What Men Value and What Women are Worth” she examines the unacknowledged and unaccounted labor of women on a global scale and makes visible these contributions. Part of what this reflection seeks to do is take a closer look at what makes this conference run, and at what cost. Acknowledging this aspect of the conference is also to ask why is this the case? Why is it that more men are not contributing more time and energy to making this site possible?

2012 Planning Committee

Jen Delos Reyes-Director

Crystal Baxley- Assistant-director

Travis Neel and Grace Hwang- Administrative Assistants

Ally Drozd, Sandy Sampson, Lexa Walsh, Ariana Jacob- Facilitators

2013 Planning Committee

Jen Delos Reyes-Director

Crystal Baxley- Assistant-director

Grace Hwang- Administrative Assistant

Lexa Walsh- Food programming coordinator

2014 Planning Committee

Jen Delos Reyes

Director

Kerri-Lynn Reeves

Programs Coordinator

Mirana Zuger

OE Assistant/SPQ

Sandy Sampson

Laura Sandow

Housing + Transportation

Gemma Turnbull

+

Alex Winters

Social Media

Ariana Jacob

Dialogue

+

Sheetal Prajapati

Lunch convos

Eliza Gregory

Welcoming Committee