Two Images and Ten Years Between

This my favourite picture of Jen Delos Reyes–I love the “you are interrupting me and I am busy, look.” In this context I am assuming that she needs no introduction, she is the reason after all that the Open Engagement (OE) conference came to be. She’s up on a ladder tracing the wall text for “Our Inconvenient Truth” for the finale of Come Together, a three week residency at the Kitchen in the summer of 2006 that brought together over a dozen socially engaged artists from all over the world to work together, learn together, and maybe most importantly for Fletcher, play together. Harrell Fletcher’s Come Together had us sitting in circles, writing on butcher paper, bending and folding in yoga classes, eating raw vegan food, playing basketball and baseball.

Many claim that artists are bad at sports, but I would qualify that by saying some are awesome at team sports: collaboration––in whatever form––is a team sport, and it formed the core of Come Together (of course, it’s implied in the title! nevermind the Beatles reference). We worked with each other and with the more established artists who inspired our projects. Our lectures came from artists such Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Emily Jacir, Paul Ramirez Jonas, all of whom have been keynotes at OE. They spoke about their work in the world, and we all debated what was at the time a nascent field and discourse––what is community, what are the techniques of engagement and so on. We hung out in Chelsea and walked under the High Line, which had yet to be redeveloped into the gentrified theme park of condos it is today. We collaborated with seniors from the local senior centre for our remake/re-enactment of Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth. Harrell assigned us each parts of the documentary to recreate in whatever way we and our resident collaborators saw fit. Emily Jacir and Lee Walton gave us assignments. Jen’s project was called Lost Dogs based on a quote Emily had given her. It was Jen’s way of connecting place––Chelsea to Palestine–to what we hold dear. Ask her about it when you see her; it’s pretty poetic.

Several artists from Come Together have made careers for themselves—Aaron Hughes, Macon Reed, Sam Gould, and many more. Jen stands out to me for obvious reasons now but at the time she was unassuming. But I remember her as quiet, and I understand now it was because she was the one listening, gathering thoughts, making connections to community organizing, radical pedagogy, all which would contribute to her master’s project––Art After Aesthetic Distance, the first iteration of OE. Come Together may have been Harrell’s brainchild, but Jen’s vision and organizing grew Open Engagement into a site where she could bring people together who were working in similar capacities with their art and community work. Conferences are usually pretty dull, but with OE she offered an alternative to the traditional conference format in favor of new forms of exchange––games, singing, and potlucks, for example. She related this to me: “at the time there wasn’t a site to discuss this work, there wasn’t support for these practices, I was engaged, other people are doing it, I needed to make that space.”

Soon after Open Engagement and when Jen started teaching at Portland State University, she and students participated in “Social Practice West” at SFMoMA. Jen and her crew were fondly called “the quirky ones”, in contrast to the CCA “heady ones,” lead by the late, great Ted Purves, and Suzanne Lacy’s Otis students who focussed more on social justice. This trifecta built much of the foundation of this “new” field of practice.

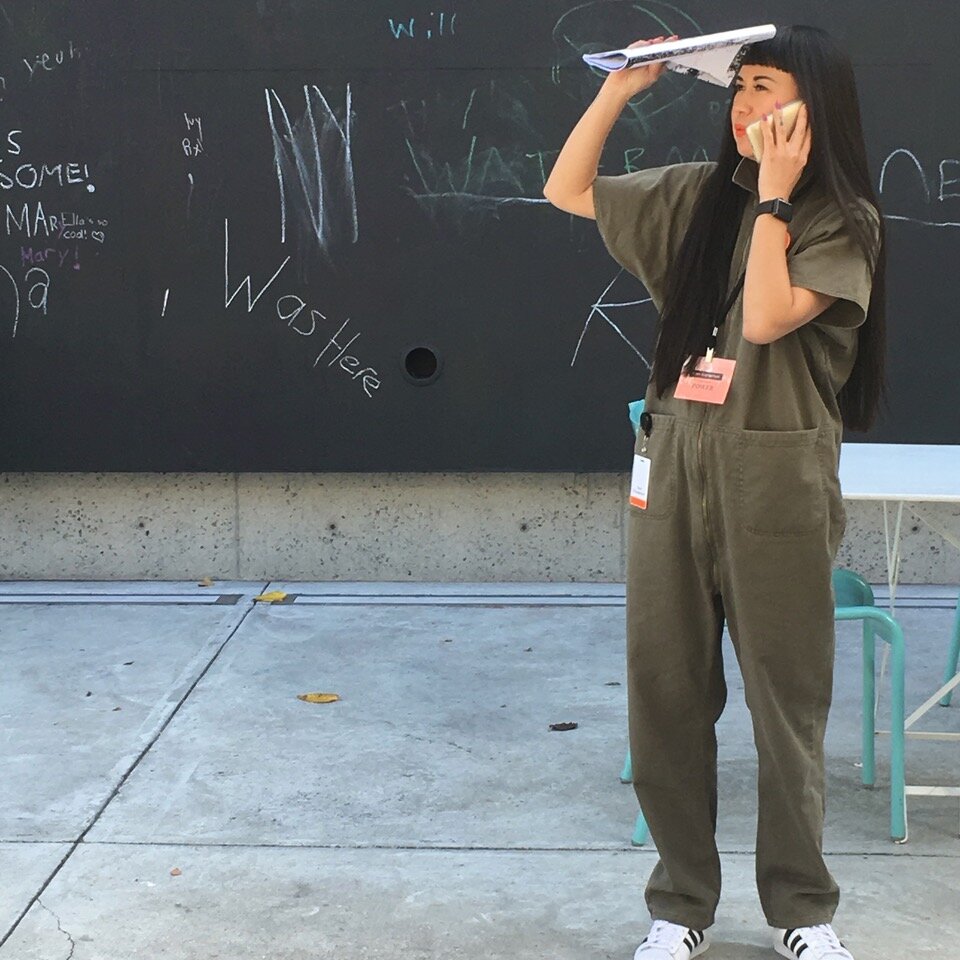

I took this picture 10 years later at OE in Oakland, 2016. I imagine that Jen’s watching art creep up on utopia at the horizon.

Much has changed in those 12 years. OE has grown, had growing pains, and has begun aligning itself with urgent social and political concerns. Some of the more prominent debates have faded into the background, some remain. Sometimes it feels less like art and more like politics or activism, but that’s OK. Artists think of efficacy, ethics, and social justice more now, which they should if they work with communities or form provisional publics.

A few times over the years I’ve caught Jen in momentary repose and asked her to reflect on OE’s development and her role as its founder and director. The conversations haven’t always been comfortable, and at times she seemed guarded, less playful than I remembered. I imagine this has to do with constantly having to defend herself or her choices (or her team’s) curatorial choices or omissions. OE has been responsive to critiques (such as MTT tally), but some of us also lament the whimsy and intimacy lost over the years. The quirky ones have grown up with the field.

Working with institutions becomes a necessary for sustainability. And while this may take the perceptible edge off radical practices, it also advances and funds those practices. Artist Jeanne van Heeswijk famously declared, “Instrumentalize me!” and Nato Thompson works strategically with institutions to push art and politics onto different registers. To think that OE could have stayed grass roots seems naive, to think that social practice wouldn’t grow in popularity through educational programs, conferences and residencies dismisses the urgency in which artists view the world. Jen works with institutions and sees them as a medium. This way the field grows in ways that support new and emerging cultural workers, and creates spaces where they work alongside more established artists in the field. In this way OE has not changed. In this way, the residue of Come Together remains.

I pulled a thread from a discussion from Social Practice West when I asked Jen about “the agency of the artwork.” She replied, “the ability of artwork to do something beyond what the artist can do, to affect change, to change people.” Jen feels the fact that OE keeps happening tells her it’s doing what she wants it to do – “bringing people together, people finding their people.” She now sees OE as less of an art project but more as an extension of her community organizing and expansive pedagogical approaches to life and art. I want to consider for a moment Open Engagement as an artwork so I can understand how its agency forms its legacy––a space for other people to speak, for others to listen, and for everyone to act.

Bio:

Gretchen Coombs lives and works in Brisbane, Australia, where she teaches in the School of Design at Queensland University of Technology. Her interests include art and design criticism/activism.